June roundup

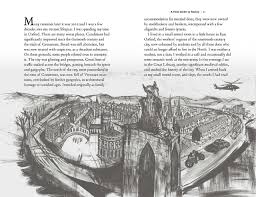

June was a pretty solid reading month, despite a bit of a weak start. Here’s my now regular round-up (and a lovely illustration to kick things off with).

A Different Sea, by Claudio Magris and translated by MS Spurr

I’ve already done a pretty thorough write-up of this one, here, and it’s fair to say I respected it more than I enjoyed it. It’s an extremely well written examination of a life lived according to philosophical ideals and without attachment, and how in fact that life becomes an exercise in selfishness and futility.

Magris is most famous for his non-fiction, and he has a lovely prose style so I don’t rule out returning to him. Probably not for a little while though.

He names his boat Maia, a small ten-footer, just big enough to venture out to sea with its white sail – the veil of Maia. The haze shimmering in air and on water on certain afternoons is either the final veil drawn over the pure present of things, or is already perhaps in itself, pure present. The sail glides over the sea, slips through a cleft in the horizon, and falls into a milky blue bound by no shore. Summers open out and solidify. Time rounds out like blown glass in water.

Super Extra Grande, by Yoss and translated by David Frye

I was so looking forward to this. It’s a Cuban science-fiction novel about a vet specialising in enormous alien animals. As the book opens he’s literally waist deep inside the intestines of some vast sea-creature that has unknowingly swallowed a valuable bracelet. He lives in a sprawling galaxy where humanity is just one of several intelligent races and there’s a sense of exuberant fun to the whole thing.

Stylistically it’s interesting as the humans of the future speak Spanglish, leading to sentences like:

“Boss Sangan, please mira, check. Ves now. Si the damn bracelet of the gobernador’s spoiled wife be there, us probablemente leave.”

And then:

“Agua here smell muy strange después del morpheorol y el laxative. Hoy not be buen dia for el tsunami bowel cleanse.”

All of which I loved for its sheer inventiveness (though it helps I have some Spanish).

The trouble is the style also consists of lots of short sentences.

Punchy phrases.

Frequent comic asides.

Which I find wearying as it gets repetitive fairly quickly. There also seems to be a strong strand of adolescent wish fulfilment here. The protagonist has to work with two former assistants, both extraordinarily beautiful women who are still in love with him. One is an alien with “six splendid breasts”. The other is a Maasai with filed teeth, his “black panther”. They’re more pin-ups than people.

Shortly after they’re introduced we get asides from the first person narrator opining on women. Women, apparently, “are like cats … When you call them they don’t come, and when you don’t call them, there’s no way to get rid of them.” “I guess there’s some strange part of the female psychology that simply can’t stand being ignored by a male…” and predictably “the two … females were starting to act jealous of each other”.

As the saying goes, I can’t even. I bailed at about fifty pages in. I loved the Spanglish, but I just don’t have the lifespan to sit while someone (real or fictional) lectures me on what women are like. Particularly in staccato phrasing.

The Great Fortune, by Olivia Manning

So far it hadn’t been a great June. This was the turning point. I wrote a full piece about it here but in short this is a marvellously evocative account of a new marriage against the backdrop of a city, country and continent on the eve of war.

It’s well written and has some distinctly memorable characters (well balanced against a larger number of less interesting ones). It also has that rather wonderful gossipy quality of much mid-twentieth Century English fiction where it feels like you’ve become part of a social set with everyone’s dramas being acted out in front of you (see also, Anthony Powell).

It’s the first of a multi volume sequence (see also, again, Anthony Powell…) and should keep me fairly busy for much of the rest of the year.

A Certain Smile, by Françoise Sagan and translated by Irene Ash

Not a million miles away from Bonjour Tristesse in style and substance I admit, but then why should it be? I’ll be doing a full write-up of this one so this will be brief. In the meantime Jacqui Wine’s piece on it is here.

Essentially, a young woman embarks on an affair with an older married man. She hopes to keep things uncomplicated and fun, without unduly hurting her boyfriend or his kind and likable wife. Of course, things won’t be quite so simple.

“… there was something in me that seemed destined to follow the well-shaved neck of a young man …”

It’s sleek and stylish and cynical and if novels smoked it would smoke Gauloises, outdoors while sipping coffee but not eating anything. I loved it.

The Magician, by W. Somerset Maugham

Apparently the rule is that one shouldn’t read any pre-Of Human Bondage Maugham. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but this is the one immediately preceding Bondage and while it’s not bad, it’s not great either.

Maugham met Aleister Crowley briefly in real life and decided to use him as inspiration for a novel, here in the form of the sinister Oliver Haddo. The main characters, all of whose names now escape me, consist of a beautiful young woman, her serious fiancé who is a skilled and increasingly eminent surgeon, the woman’s plainer friend and an older doctor who happens to be knowledgeable for reasons of plot in occult matters.

Anyway, Haddo falls in with them, he offends the young woman by kicking her dog, the doctor beats him up and Haddo exacts a terrible vengeance for the slight. If you picture Charles Gray from The Devil Rides Out as Haddo you wouldn’t be going too far wrong (they don’t look alike but the manner is pretty much spot on).

It’s clearly well researched and it’s reasonably well written with some effective scenes, but ultimately there just doesn’t seem much point to it. Dennis Wheatley wrote the same sort of thing and with a much worse style, but much more fun.

Aleister Crowley later reviewed it and didn’t take to it at all, perhaps unsurprisingly. Maugham went on to write better. One for Maugham completists or for horror fans who may well enjoy its gothic atmosphere (though who may also, like me, spot where it’s going far too early).

Holt House, by L.G. Vey

Continuing with the horror theme this is the first release from the Eden Book Society. Ostensibly a reprint of a lost novel from 1972, it’s actually one of a series from a pool of authors each of whom writes under a pseudonym, but without the reader knowing which author has which pseudonym.

The authors involved are an impressive bunch, including Andrew Hurley and Aliya Whiteley and several others whose names I recognise even though I haven’t read them yet. Naturally I’ve no idea which of them is channelling the spirit of L.G. Vey…

Holt House itself is a chilling novella about a man haunted by something he once saw in a house which doesn’t seem to have changed at all in the intervening decades. What is the horror though? Is it the house? Is it the kindly Mrs Latch who lives there? Is it the man himself? The answers shift and never entirely settle.

Oddly enough, I’ve watched a fair bit of 1970s TV horror over the past couple of years. For some reason there were a lot of TV plays back then many of which were firmly in the horror genre. Two elements stand out to me from those old shows: firstly, they were usually exceptionally bleak by modern standards; and secondly they were much more concerned with social issues than one might expect.

Some addressed ethical treatment of animals. I saw one recently that critiqued the complacency of people living well in rich countries while those in poor ones starved. Feminism and the role of women was often explored. Horror in this period was often used as a vehicle for social criticism.

Holt House continues that, dealing here with male violence among other things and that concern felt to me both current but also of the period. There’s also a lovely little bit of SF that creeps in at one point which feels very 1970s. All that and the whole thing is deliciously creepy and atmospheric. Accomplished stuff.

One final word. Eden do both ebook and physical subscriptions. If you jump on board get the physical (or get both). The book fits nicely in the hand and is a very comfortable read. Oh, and a post-final word, David Hebblethwaite also reviewed this here.

A Field Guide to Reality, by Joanna Kavenna

This is going to be hard to describe. Essentially the narrator, a waitress in Oxford who has just recently lost her father, was friends with an Oxford don who now also dies but who leaves behind a box with her name on it and supposedly inside his master work – his “Field Guide to Reality”. The box is empty.

Urged on by his surviving academics, she goes on a sort of vision quest through a motley array of Oxford eccentrics trying to discover this great lost work, this summation of reality itself. It’s a descent into Oxford as underworld.

The quest is of course impossible. However, along the way Kavenna explores the history of theories of the nature of light, from medieval theoretician Robert Grosseteste through Newton all the way up to modern quantum physics!

It’s heady stuff! Unfortunately, I was already reasonably familiar with the subject matter which meant that when there was a three page digression on fifth Century Greek philosopher and scientist Hypatia I was thoroughly bored as I already had a pretty good idea of who she was and of her life.

Now, it’s fair to say that Kavenna knows more of Hypatia and I suspect of everything else in the book than I ever will! Mercifully, she doesn’t put in all she knows. Less happily that meant that often what she did put in I did know. Kavenna also brilliantly describes Oxford, which I didn’t go to so much of that was a bit lost on me. If you did go to Oxford I suspect you’d love this book.

Imagine for a moment a contemporary Alice in Wonderland, but with Alice a grown woman and the mad inhabitants of the world through the looking glass replaced by Oxford dons and theoreticians. Then you’re starting to get there.

The book comes with absolutely wonderful illustrations. Physically it’s really quite beautiful! It also comes with an unfortunate predilection to overusing exclamation marks. It’s been exceptionally well reviewed so if it sounds at all interesting you might want to at least look at a copy in a shop to see what you think. It’s larger than I have words here to describe. In the meantime, here’s an interesting interview with the author in the Guardian. And here’s another of the illustrations (the first is at the head of this post):

Cove, by Cyan Jones

I finished the month with Cynan Jones’ leanly muscular novel Cove, about a man lost at sea after surviving a lightning strike. Grant reviewed it well at 1streading here and I don’t have much to add to his piece. As with Jones’ The Dig it’s ruthlessly pared back both in terms of prose and story. It’s my second by Jones and I expect to read more by him. In fact, I expect to read everything by him.

So that’s my June. I read eight books, four of which I really liked, one of which I abandoned and three of which weren’t for me but might be for someone else. I’m pretty happy with that. The Kavenna was an unexpected misfire for me, but I don’t regret reading it. It tried something new, and while it didn’t work for me on this occasion I’d far rather that than read the same thing every time.